If you’ve been wondering what we’ve been up to in the past month, we decided to map it to give an idea of the vast area we covered, serendipitously a giant spiral from coast to coast of southern Mexico. We covered over 3000 kilometers on buses, the backs of pickup trucks, and small fishing boats across 4 Mexican states. We visited Afro-Mexican pueblos from the north of Veracruz to the Istmo and Costa Chica of Oaxaca and Guerrero, with the goal of understanding how the land-based and spiritual wisdom of the African ancestors informs the lives of the people. Our secondary goal was to have access to internet for several hours each day to bust out a serious quantity of Fulbright and Soul Fire Farm work, which you are encouraged to explore, use, and support. Full photo album is here. Read on…

If you’ve been wondering what we’ve been up to in the past month, we decided to map it to give an idea of the vast area we covered, serendipitously a giant spiral from coast to coast of southern Mexico. We covered over 3000 kilometers on buses, the backs of pickup trucks, and small fishing boats across 4 Mexican states. We visited Afro-Mexican pueblos from the north of Veracruz to the Istmo and Costa Chica of Oaxaca and Guerrero, with the goal of understanding how the land-based and spiritual wisdom of the African ancestors informs the lives of the people. Our secondary goal was to have access to internet for several hours each day to bust out a serious quantity of Fulbright and Soul Fire Farm work, which you are encouraged to explore, use, and support. Full photo album is here. Read on…

-

Raise the Roof for Food Justice @ Soul Fire Farm – Our $100K fundraiser to build a barn for food distribution and programming

-

Global Sustainable Food Curriculum – a semester-long introduction to agroecology through the lens of campesinos in southern Mexico

-

Upcoming Speaking Engagements by Leah/Soul Fire Farm on Sustainable Agriculture and Food Justice

-

Pasture Raised Chicken for Sale. Quantities are limited and going fast (and that’s not just a sales pitch). Pre-order here.

-

Community Workdays and Skillshares are: June 21, July 25, August 15, September 26, October 17. The

workday runs from 8 AM -1 PM followed by a potluck lunch, 1-2:30 PM. All are welcome. Please RSVP by email. Check the weather report and dress appropriately.

workday runs from 8 AM -1 PM followed by a potluck lunch, 1-2:30 PM. All are welcome. Please RSVP by email. Check the weather report and dress appropriately. -

We are looking for people savvy with social media, especially twitter, to support us during our upcoming crowdfunding campaign.

-

Additional volunteer opportunities listed here.

-

Summer SOULstice Party, June 27, 5pm. Come celebrate the gifts and abundance of living on this blessed planet and our beautiful community. Performances in the woods, dance party, camping, community.

Love Notes from Abroad

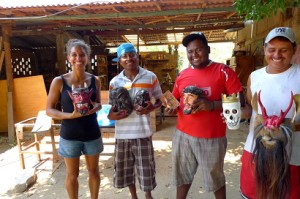

In the Afro-Mexican pueblo of Coyolillo, Veracruz, there is a 500 year old tree named “Nascali.” She is adorned with gifts of flowers, candles, and a cross. Our friend Don Luis explained that the community is very religious and identifies as Catholic, yet the forms of worship show African influence. As is the case across Mexico, the saints are the focus of spiritual devotion and each pueblo has its patron saint. In Coyolillo he is the farmer’s saint – San Isidro Labrador (who reminds me of the Haitian farmer loa Azaka.) During festivals, the community travels together to the mountain top and to the old tree for worship. The community specializes in the carving of wooden masks for ceremony, though this art is being lost. Only two accomplished elder mask-makers remain. An art that persists among the youth is a popular style of clothing made from diverse and colorful fabric pieces integrated into a patchwork, as is common in Ghana “pizi pizi.” As far as agriculture, this pueblo largely adopted North American indigenous practices of growing chayote, beans, and corn.  The two definitively African crops are plantain and camote, the former prepared as torta de platano (akin to pen patat in Haiti and other starch based breads across the Diaspora). For many years, there was no bus service to Coyolillo because neighboring pueblos of “hueros” (Euro-descendants) feared intermarriage with Afro-descendants. This isolation is partly responsible for the preservation of distinctive aspects of the culture and physical appearance of people in the pueblo.

The two definitively African crops are plantain and camote, the former prepared as torta de platano (akin to pen patat in Haiti and other starch based breads across the Diaspora). For many years, there was no bus service to Coyolillo because neighboring pueblos of “hueros” (Euro-descendants) feared intermarriage with Afro-descendants. This isolation is partly responsible for the preservation of distinctive aspects of the culture and physical appearance of people in the pueblo.

The Afro-Mexican towns of Corralero and Collantes, on the southwestern coast of Oaxaca, were built on hacienda slavery to produce cotton, sugarcane, and cacao. The hacienda economy persisted long after the official outlawing of slavery and we visited the remains a cotton processing factory that operated into the late 1800’s. Terrestrial agriculture does not offer much by way of example for those interested in sustainable farming – mostly chemically intensive export crops of papaya and tomato destined for Walmart, coaxed from soil barren of trees and hot with the smoldering coals of slash and burn clearing. The fishing and shellfish harvesting is another story. Here the “arte de pesca” is notable African, from the design of nets and woven traps to the shape of the small fishing boats. Fishing is still practiced on a small scale and the harvest forms the basis of the diet. We had the opportunity to take a swim with some fisherman where the river meets the sea and were struck by the temperature of the water, much hotter than the sweltering air, and also by the fearlessness of the locals as we shared the water with the crocodiles.

export crops of papaya and tomato destined for Walmart, coaxed from soil barren of trees and hot with the smoldering coals of slash and burn clearing. The fishing and shellfish harvesting is another story. Here the “arte de pesca” is notable African, from the design of nets and woven traps to the shape of the small fishing boats. Fishing is still practiced on a small scale and the harvest forms the basis of the diet. We had the opportunity to take a swim with some fisherman where the river meets the sea and were struck by the temperature of the water, much hotter than the sweltering air, and also by the fearlessness of the locals as we shared the water with the crocodiles.

Our hosts in Collantes were a group of young men that organized themselves to preserve and celebrate the traditional dances of the community. They perform Danza de los Diablos, a story-dance that their ancestors revived during slavery to celebrate their own African God while the ones who called themselves masters were celebrating the white God. When the hacienda owners learned of this dance, they accused the celebrants of worshiping the devil (diablo.) Of course this was not the case, but the name stuck. The dance tells the history of the people with elaborate movements, costumes, and masks. Two-year-old Dylan, son of the dance group organizer, demonstrated for us that he had already learned and internalized the basic steps.

Our hosts in Collantes were a group of young men that organized themselves to preserve and celebrate the traditional dances of the community. They perform Danza de los Diablos, a story-dance that their ancestors revived during slavery to celebrate their own African God while the ones who called themselves masters were celebrating the white God. When the hacienda owners learned of this dance, they accused the celebrants of worshiping the devil (diablo.) Of course this was not the case, but the name stuck. The dance tells the history of the people with elaborate movements, costumes, and masks. Two-year-old Dylan, son of the dance group organizer, demonstrated for us that he had already learned and internalized the basic steps.

We were blessed to be welcomed into several other pueblos. In Cuajinicuilapa, Guerrero, we spent the afternoon with the director of the AfroMexican museum and had a passionate conversation about the ways slavery has taken new forms in modern days. We lived for several days with a family of African drum/dance  teachers in their adobe house with aerial silks and composting toilets outside of Xalapa. We spent time at a Montessori school and Equimite Biodynamic Farm in Coatepec. We explored the mangroves of Sontecompan and swam against the rules in the “mar del fondo” on the coast of Oaxaca.

teachers in their adobe house with aerial silks and composting toilets outside of Xalapa. We spent time at a Montessori school and Equimite Biodynamic Farm in Coatepec. We explored the mangroves of Sontecompan and swam against the rules in the “mar del fondo” on the coast of Oaxaca.

As our time here comes to a close, it is interesting how events once notable have become commonplace. We are used to riding in the back of a pickup truck (camioneta) packed with chickens, dogs, a wheelbarrow, bucket of pig slop, and 12 people. We are not surprised to see military police “protecting” the people from a wild ocean by standing along the beach with machine guns. A meal without fresh tortillas is now incomplete. Wearing a bathing  suit is really strange when you could just go in with your jeans and t-shirt. Shower curtains are a luxury. Rushing is absurd. Extended families belong together.

suit is really strange when you could just go in with your jeans and t-shirt. Shower curtains are a luxury. Rushing is absurd. Extended families belong together.

I asked the family what they learned here and how they have grown. The kids responded concretely that they can speak Spanish and walk long distances, and Neshima learned one harp piece in Xalapa. While true, I have also appreciated how close the two have become, laughing and joking on long bus rides and falling asleep on each others’ shoulders. The whole family is closer than ever and we anticipate with sadness having to return to a life of work and school, apart from one another. Personally, I was struck by how powerfully I felt connected to the land, especially in the mountains. I felt affirmed in choosing the life of a campesina and felt with clarity that I belong on the land. I was also struck by the ease with which I could move through communities in  Costa Chica, where people assumed I was a local, similarly mixed Afro-Euro-Indigenous. Jonah had a humbling experience, touching the reality of the immense work to be done for global food sovereignty and how little we know personally, even after 20 years in the work. We all made deep and lasting friendships and found collaborative partners for future projects. We are nerdy excited to try new varieties of corn, beans, and squash gathered from the pueblos we visited and to make our own nixtamal and tortillas. We are reminded that collective, communal ways of life are not just possible, but thriving ubiquitously. Our hearts are open and our hands are ready.

Costa Chica, where people assumed I was a local, similarly mixed Afro-Euro-Indigenous. Jonah had a humbling experience, touching the reality of the immense work to be done for global food sovereignty and how little we know personally, even after 20 years in the work. We all made deep and lasting friendships and found collaborative partners for future projects. We are nerdy excited to try new varieties of corn, beans, and squash gathered from the pueblos we visited and to make our own nixtamal and tortillas. We are reminded that collective, communal ways of life are not just possible, but thriving ubiquitously. Our hearts are open and our hands are ready.

This is Leah, your “Love Notes from Abroad” writer, signing off. Jonah will be taking the lead on the newsletter now that we are back on the farm.